Film critic Roger Ebert famously described cinema as a “machine that generates empathy” and to me that machinery is running at peak efficiency when it comes to sports dramas and romantic comedies.

As someone who doesn’t follow professional sports in real life, I’m constantly wowed by films like Moneyball (2011), Rocky (1976) and Remember the Titans (2000) that sucked me into the world of professional baseball, boxing, and high school football, respectively.

The same kind of amazement is at play when I watch a good rom com, since I generally don’t dwell on the interpersonal lives of those outside of my friends and family.

Richard Loncraine’s Wimbledon (2004) was largely able to bridge that divide on both fronts.

Not only did Loncraine and his team create a couple I actively rooted for, but they also managed to hook me in with the competitive aspect of a sport that I couldn’t care less about (tennis).

Plus, the writing team should be commended for the way they turned this genre mash-up into a core part of the plot, since the protagonist is caught between his athletic legacy and his desire to pursue a new relationship.

While there are some annoying remnants of 2000s filmmaking at play, Wimbledon is still an immensely charming affair that should unify fans of sports movies and romantic comedies, as long as both parties come in with an open mind.

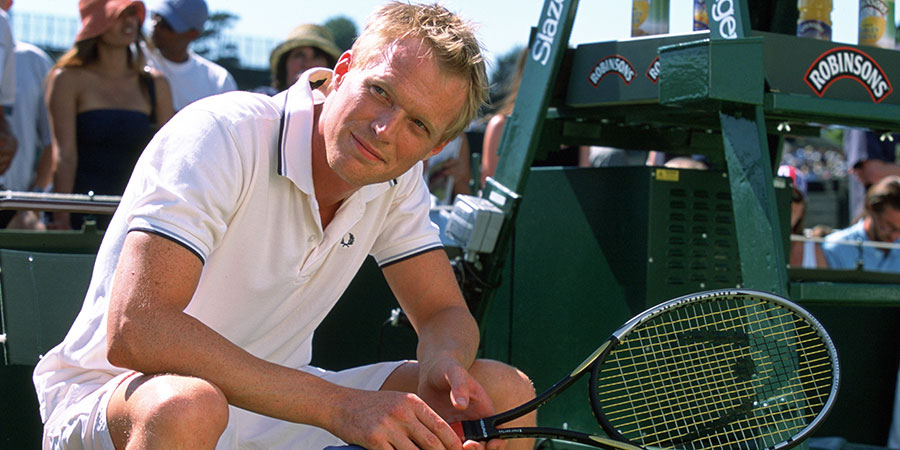

The plot of Wimbledon follows Peter Colt (Paul Bettany), a journeyman tennis pro who is at the end of his career and decides to enter the renowned UK tournament for the final time.

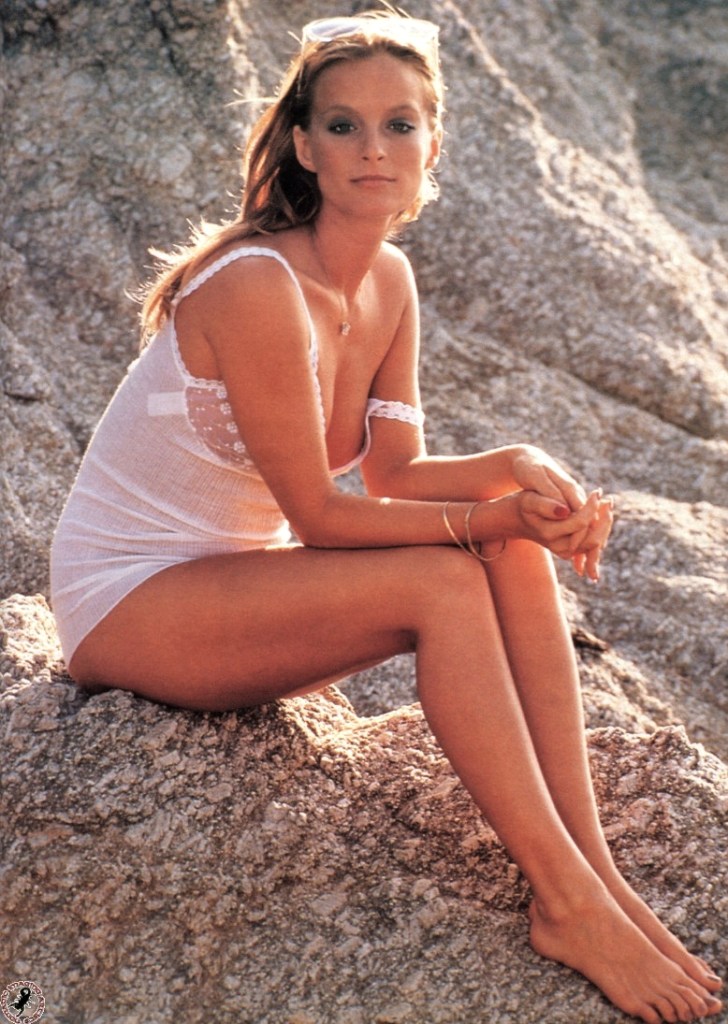

Despite going into the competition with limited expectations, Peter quickly finds that his fortune has changed once he meets and begins a relationship with up-and-coming American tennis star Lizzie Bradbury (Kirsten Dunst).

Not only is he playing better on the court, but Peter’s growing feelings for Lizzie allow him to envision a happy life beyond tennis for the very first time.

Unfortunately, the high-pressure environment of Wimbledon, and the media circus surrounding it, threatens to tear these two apart as the tournament reaches its conclusion.

Of course, the first inevitable hurdle that most romantic comedies must clear has to do with the leads and whether or not they are a believable on-screen couple.

Luckily, Bettany and Dunst sell you on this idea as soon as they first lock eyes in Wimbledon.

Their mutual attraction and chemistry is palpable, so much so that you don’t question the pair hooking up less than 20 minutes into the movie (a development that other filmmakers would have saved for the, er, climax of the story).

Bettany’s performance is particularly impressive given that Wimbledon marked his first major role in a romantic comedy.

During a 2018 interview with GQ, Bettany revealed this part proved extremely difficult, as he wasn’t prepared to take on a character who is required to be “relentlessly charming” in every scene.

But whatever difficulties Bettany was experiencing behind the scenes didn’t follow him in front of the camera, as his underdog tennis pro remains a consistently engaging presence who is easy to get behind.

Dunst is even better equipped to handle this material, having recently cut her teeth on a range of comedies and romantic dramas like Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999), Bring It On (2000), and Crazy/Beautiful (2001).

Because of this, she effortlessly slips into the role of a firecracker love interest, while also maintaining a strong sense of agency that makes her an interesting character in her own right.

Much of the pair’s likability should also be credited to Wimbledon’s trio of screenwriters (Adam Brooks, Jennifer Flackett, and Mark Levin), who managed to craft a whole cast of characters that remain grounded despite engaging in some heightened romantic comedy hijinks.

Peter Colt (Bettany) is a prime example of this, since a lesser film would have taken the easy route and presented audiences with a complete screw-up to garner more sympathy right off the bat.

Instead of being saddled with a drinking problem or some inherent klutziness, Peter’s inner conflict is rooted in his fear of becoming irrelevant in a sporting world that is leaving him behind.

And despite his oblivious foibles, Bettany remains a cool operator when it comes time to chat with reporters or literally fight for his lady’s honour at a party, presenting a character who is aspirational without being unrealistic.

I know this sounds like basic screenwriting, but a surprising number of romantic comedies screw up this formula, where the characters are presented as one note or cartoonishly flawed in order to generate cheap laughs.

One such famously underwritten rom com archetype is the love interest’s disapproving father, whose dislike of the protagonist often borders on psychotic.

However, Sam Neill injects some much needed subtly into this kind of character in Wimbledon.

While he definitely serves as an obstacle that Bettany must overcome to court Dunst, Neill remains soft-spoken and completely reasonable from the get-go, explaining that his daughter’s full attention should be on the tournament if she wants to succeed as a tennis star.

This concern mirrors Bettany’s lingering anxiety about his own legacy in the sport, creating a shred of understanding between the two opposing characters that was a nice touch.

That being said, the film’s main antagonist is the one character in the cast who remains completely underwritten.

As Bettany’s American tennis rival, Jake Hammond isn’t given any opportunity to play anything other than an arrogant, sneering villain, who slut shames women off the court and (accidently) assaults small children while on it.

These antics do succeed in getting you to hate Hammond, but it doesn’t take away from the reality that his one-dimensional character sticks out like a sore thumb.

A similar lack of subtlety is on display during the early one-on-one tennis scenes, which feature some garish computer-generated trickery.

Instead of focusing on the athleticism of his actors, Loncraine uses these digital camera movements to follow the ball from one side of the court to the other, harking back to that dark period of the mid 2000s when most directors hadn’t quite mastered CGI as a story-telling tool just yet.

Thankfully, Loncraine reels back his usage of this virtual reality hell as the film goes on, letting Bettany and Hammond take centre stage for the grand finale.

And by that point, the writers had already laid the groundwork necessary to get me invested in this big showdown, tying Bettany’s success in the tournament to many of the supporting characters in the cast.

Not only does his relationship with Dunst ebb and flow in tandem with each successive match, but so do the financial endeavors of his brother (James McAvoy), his agent (Jon Favreau), and the emotional reconciliation of his parents (Bernard Hill, Augusta Colt).

And by having all these characters show up to cheer him on in the finals, alongside the rest of England watching on TV, Loncraine creates an organic underdog story that doesn’t seem phony or forced.

Because of this, I can look past a lot of the film’s shortcomings, like its bland villain, sporadic use of bad CGI, and dated soundtrack that features the kind of radio-friendly soft pop that’s best left in the 2000s.

All that noise fades into the background for what ends up being a solid sports-romantic comedy hybrid that focuses on the human element first and athletic spectacle second.

If you feel like the filmmakers’ priorities are backwards when it comes to this material, then Wimbledon might not be for you.

But for someone like myself who gravitates towards the theatrical elements of professional sports, but not the games themselves, this movie hits the right notes and is an easy recommendation.

Unfortunately, Wimbledon wasn’t compelling enough to convince me to watch the actual tournament this coming July.

That being said, I might change my mind if this year’s event features another relentlessly drunk Woody Harrelson cheering from the sidelines.

That’ll be must-see TV.

Verdict:

7/10

Corner store companion:

Kiwi Strawberry Vitamin Water (because it’s a refreshing treat, as long as you’re prepared to deal with the sugar rush)

Fun facts:

-Release date: Sept. 17, 2004

-Budget: $31 million

-Box office: $17,001,133 (US and Canada), $41,682,237 (international)

-Scenes from this film were shot during the actual 2003 Wimbledon tournament, with real-life spectators and officials featured in the background. This is the only time this kind of filming has been allowed in the tournament’s history.

–Wimbledon features several actors who have played famous Marvel Comics characters on the big screen. This includes Dunst (Mary Jane, Spider-Man), McAvoy (Professor X, X-Men), Favreau (Happy Hogan, Iron Man), and Bettany (Jarvis/Vision, various). In fact, Bettany claims that Favreau cast him as Jarvis in the first Iron Man film because of their time shooting Wimbledon together.

-Bettany spent eight months training to prepare for his role as a tennis pro, having never picked up a tennis racket beforehand. He credits Wimbledon champion Pat Cash with teaching him how to play.

-The career trajectory of Bettany’s Peter Colt parallels real-life Croatian tennis pro Goran Ivanišević, who remains the only wild card singles player to win a Wimbledon title (having done so in 2001 while being ranked 125th in the world).

-Surprise cameo(s): Renowned tennis pros John McEnroe and Chris Evert (playing themselves) provide play-by-play and colour commentary throughout the film.