Lately, I’ve been getting this sinking feeling that certain genres of film are becoming completely irrelevant to modern audiences. This endangered species list includes any thriller or drama that touches on contemporary U.S. politics, given how chaotic, fractured, and patently absurd the real-life machinations of the current administration are. After all, how can a Hollywood screenwriter compete with the sheer ludicrousness of SignalGate or top the cartoonish villainy exhibited by a shifty interloper like Elon Musk?

In this context, Antoine Fuqua’s Shooter (2007) seems pretty tame by comparison. This is because the film’s U.S. government baddies are at least marginally intelligent and vaguely discreet when it comes to enacting their evil plans, not at all like their modern, real-world counterparts.

But regardless of the differences between Bush and Trump era politics, these conspiracy-themed thrillers can be a lot of fun, as long as they have a decent script, smooth pacing, and some tight direction.

Shooter definitely excels in a few of these areas, providing the perfect kind of disposable action movie fluff to watch on a lazy Sunday afternoon alongside your dad.

Unfortunately, the film is also weighed down by a weak lead performance and far too many genre cliches, making it hard to distinguish from the dozens of other “one man army” stories clogging up your local DVD bargain bin or drugstore book rack.

The eponymous “Shooter” in this film is Mark Wahlberg, who steps into the boots of elite Marine sniper Bob Lee Swagger. Despite being retired from the U.S. military for several years, Swagger is pulled back into service by Colonel Isaac Johnson (Danny Glover), who needs his help to thwart a presidential assassination attempt. However, the job quickly reveals itself to be a set-up, with Swagger being blamed for killing the Archbishop of Ethiopian (who was standing next to the American president during the shooting). Now on the run, Swagger must clear his name and get to the bottom of a vast conspiracy that reaches all the way to the U.S. Senate.

Like I mentioned at the top, the film’s major weak link is Wahlberg, who does very little to elevate this material above your standard action schlock.

Sure, Marky Mark pulls off the right rugged look and is convincing when he’s holding a gun. But there’s very little in his performance that helps engage the audience on an emotional level.

One moment that stuck out to me was when Swagger’s love interest (Kate Mara) tells him that the bad guys killed his dog. Rather than reacting with piercing sadness or explosive anger over the murder of his best friend, Wahlberg responds with mild annoyance, like someone just told him that he needs to replace his Brita filter.

Unfortunately, Wahlberg remains stuck in this subdued acting mode for most of the film’s runtime, offering only brief glimpses beneath his stoic persona.

I’m not suggesting he needed to break down crying every five minutes to be more relatable or whatever, but some psychological insight would have been welcome.

Maybe this could have been accomplished through casting an older actor, someone capable of bringing a genuine world-weary quality to the role.

According to IMDB, men like Clint Eastwood, Tommy Lee Jones, and Harrison Ford were all considered for the part, which sounds like a much better fit for the vibe the movie was trying to convey.

But to be fair to Wahlberg, the film’s script doesn’t do him any favours.

Despite being established as a conspiratorial shut-in (who lives in the mountains and reads the 9/11 Commission Report for fun), Swagger is surprisingly willing to trust this shadowy government figure (Glover) and fall for the most obvious frame up job of all time.

So when he’s betrayed and literally shot in the back, I was left wondering why Swagger didn’t have any contingency plans in place, since being a rigid individualist who doesn’t trust the government is one of his only defining character traits.

Plot nitpicking aside, Shooter at least delivers the goods once Wahlberg goes on the run.

While nothing approaches the tension director Andrew Davis created for The Fugitive (1993), Fuqua and his team make up for that by staging some impressive kinetic action.

This means juicy blood squibs, bright muzzle flashes, and big practical explosions, all tied together with crisp editing that makes the moment-to-moment carnage easy to follow.

The best example of this technical expertise is on display in the third act, when Wahlberg teams up with a sympathetic FBI agent (Michael Peña) to storm a rural compound full of cannon fodder enemies.

This flashy spectacle is also helped by the cast of great character actors assembled to play the bad guys.

Outside of Glover, this rogue’s gallery includes the likes of Ned Beatty as a corrupt U.S. senator and Elias Koteas as a psychopathic henchman on Wahlberg’s trail.

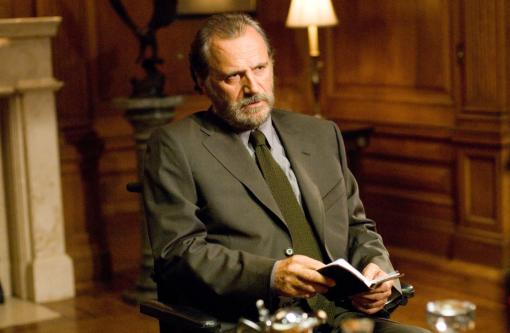

While these three are suitably over-the-top, and serve as the perfect rivals for Wahlberg’s salt-of-the-earth veteran, the movie does at least carve out some depth for Rade Šerbedžija.

The well-known Croatian actor makes the most of his tiny role as a wheelchair-bound sniper who is working under the thumb of Glover’s corrupt army colonel.

Even though most of his lines are relegated to a single exposition dump, Šerbedžija conveys a lot of potent regret and melancholy through his delivery alone, making me wish the movie was about him instead.

Unfortunately, familiar action movie tropes eventually pile up and dilute whatever unique sense of identity Shooter had going for it. Some of these trappings I’m willing to forgive, like all the bad guys not being able to hit the broad side of a barn in a firefight. But other cliches are pretty egregious and took me out of the movie. These moments include:

- Wahlberg’s soldier buddy pulling out a photo of his wife moments before getting ravaged by bullets

- Mara delicately dressing the wounds of a naked Wahlberg despite barely knowing him

- One of the bad guys delivering the “we’re not so different, you and I” speech to Wahlberg as he’s being held at gunpoint

- Wahlberg being way too cool to look back at the explosion he just set off

Many of these moments were old hat in the 1990s, so the fact that they were smuggled into a 2007 film (without anyone in production batting an eye) is very concerning.

And while Shooter is fairly generic overall, I will at least give the filmmakers credit for grounding it in the specific real-world politics of the time.

Instead of taking the coward’s way out and giving the bad guys vague motivations (as to not offend anyone), the screenwriters zero in on U.S. foreign policy being a pervasive antagonistic force.

Not only is the Abu Ghraib torture scandal mentioned by name, but most of the plot revolves around [SPOILERS] the American military covering up an African village massacre to further Big Oil business interests.

After watching my fair share of military propaganda for this blog, it was refreshing to see U.S. imperialism portrayed in a critical light, even if it is packaged in a movie where the hero solves all his problems with brute force.

In that sense, Shooter may resonate with more people in 2025 than it did in 2007, given that the current American government is explicitly threatening to annex places like Greenland, Panama, and even my home country of Canada.

I’m not suggesting that a dumb action movie like Shooter will wake people up to this growing American hegemony or shake them from the kind of political apathy that allows evil to flourish.

But if someone receives a shock to the system by noticing how these goofy movie villains are being eclipsed by the sinister actions of real-world politicians, then maybe this film is a worthwhile watch after all.

Plus, did you see that scene where Wahlberg sniped three guys while standing up in a boat? That was sick!

Verdict:

6/10

Corner store companion:

Allen’s Cranberry Juice (because when it comes to resisting U.S. imperialism, buying a Canadian food product is on the same level as watching a vaguely anti-American film from 18 years ago)

Fun facts:

Release date: March 23, 2007

Budget: $61 million

Box office: $95.7 million

-The character Bob Lee Swagger was originally created by author/film critic Stephen Hunter and first appeared in the 1993 novel Point of Impact. Hunter has written 12 books in the Bob Lee Swagger series, with the last story (Targeted) being published in 2022.

-The gun expert Wahlberg meets in the middle of the film is played by musician Levon Helm, who served as a drummer for The Band and was a 1994 inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Outside of his lengthy music career, Helm also appeared in films such as Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980) and The Right Stuff (1983).

-This film was later spun off into a TV series that ran for three seasons (2016-2018) on the USA Network. Ryan Phillippe took over the lead role from Wahlberg and the plot of the TV show revolved around the first three novels in the Bob Lee Swagger book series.

-Musical highlight: “Nasty Letter” by Otis Taylor (plays during the end credits)