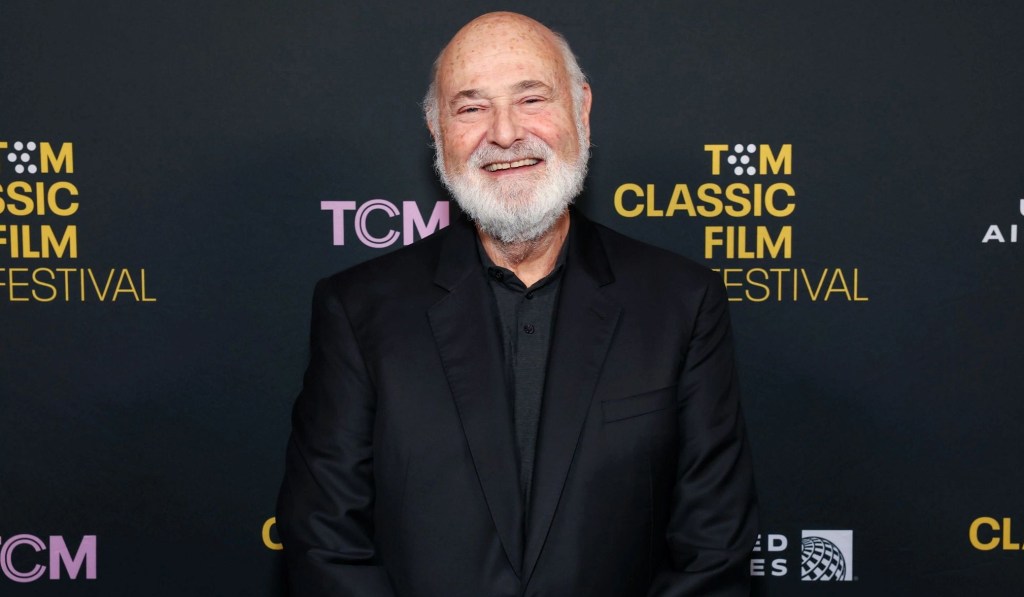

Last year was a non-stop cavalcade of horrific news, with the murder of Rob Reiner and his wife Michele (at the hands of their own son) capping off those rotten 12 months on the worst possible note.

The one thin silver lining to this grim affair was the massive outpouring of love that emerged in its aftermath, where fans, colleagues, and friends commemorated Reiner’s talent as a filmmaker alongside his strong moral fiber as a person.

From a career perspective, one of the big through lines people focused on was Reiner’s versatility as an artist. Not only was he praised for his roles in front of the camera, but Reiner’s ability to spearhead a variety of genre projects as a director also came into sharper focus.

A brief scan through Reiner’s filmography will reveal classic coming-of-age dramas (Stand By Me), fantasy adventure (The Princess Bride), romantic comedies (When Harry Met Sally…), psychological horror (Misery), legal dramas (A Few Good Men), and mockumentaries (This Is Spinal Tap).

One film that wasn’t included in a lot of these wistful retrospectives (at least from what I saw) was The Story of Us (1999), a turn-of-the-millennium romantic drama that charts the troubled marriage of a couple played by Bruce Willis and Michelle Pfeiffer.

Looking at the reviews from that time, it’s easy to see why this film isn’t held in high regard today. On Rotten Tomatoes the movie holds a dubious 28% rating based on 128 reviews, with the critical consensus slamming it as “dull” and “predictable.” The audience score isn’t much better.

However, viewing the film with fresh eyes in 2026, I think The Story of Us is a worthy addition to Reiner’s catalogue, since it manages to embody the sensitivity, humour, and humanity that tied so many of his works together.

The plot of The Story of Us focuses squarely on Ben (Willis) and Katie (Pfeiffer), whose marriage of 15 years is on the verge of outright collapse. When their two children go away to camp for the summer, the couple are left in a state of limbo, not knowing if they should stay together for the kids or just make a clean break.

Ben and Katie’s relationship history is conveyed in a largely non-linear fashion, with the first act of the film being dominated by these brief flashbacks that catch the audience up to speed. Not all of these snippets are told in chronological order, so you’re largely reliant on context clues (like the characters’ changing hairstyles) to figure out when each scene fits into the timeline.

While all this is going on, Willis and Pfeiffer also provide dueling narration from the future, looking back on their turbulent marriage with a healthy degree of hindsight.

On paper, this narrative structure sounds like a mess and, admittedly, it can be a little discombobulating at first. However, I thought the editing team managed to string these disparate pieces together in a way that complimented the story. After all, the disruptive way these short flashbacks are inserted into the film mimics how a lot of people remember the past (i.e. chopped up into disorganized peaks and valleys with flimsy connective tissue in between). Plus, this jigsaw-like storytelling method kept my brain engaged throughout, as I was subconsciously filling in the gaps as the plot progressed.

The dual narration also serves a purpose beyond just filling dead air. Outside of providing further insight into how each character views their failings as a romantic partner, the ambiguity of their dialogue leaves you hanging in suspense, since it’s not clear if they’re still married until the very end.

That being said, the film does slow down in its second act, with the interruptive flashbacks being dialed back considerably. This breathing room allows Willis, Pfeiffer, and the script to take centre stage, for good and for ill.

On one hand, Pfeiffer puts her all into the role of Katie. She is totally believable as a woman who feels overwhelmed and consumed by her role as a mother, so much so that she doesn’t have anything left to invest into her role as a wife.

Willis, meanwhile, is significantly less believable as the goofy sitcom dad. It’s not like he hasn’t demonstrated some acting range throughout his career, managing to shed that macho, tough guy image for movies like The Kid (2000) and The Sixth Sense (1999). But this role in The Story of Us seems far beyond Willis’ capabilities, especially whenever he’s asked to put on a funny voice or anchor an extended comedy bit.

At least the two of them work well together as a dysfunctional couple. Any scene involving Willis and Pfeiffer arguing or suffering through an artificially cordial dinner with their children is tense, with so much unspoken conflict bubbling beneath the surface.

The script, similarly, has its good and bad moments.

Sometimes, it seems like the writers are lazily treading into Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus type territory when the characters discuss how each sex views relationships. An early scene involving Ben and Katie’s respective friends talking about this subject at separate lunch dates seems like the cast of Seinfeld and Sex and the City are being artificially cross cut together.

Additionally, it’s kind of lame that the film’s overriding conflict ultimately gets resolved [SPOILERS] via a profound declaration of love from one of the characters. It just seems like a cheap and easy way to wash away the complicated relationship dynamics that were being explored for the previous 90 minutes.

Still, the script manages to shine in some other key areas.

For one thing, the film wisely resists the urge to dive into outright melodrama or soap opera shenanigans as a shortcut.

Both Willis and Pfeiffer never committed infidelity, and they don’t resort to hurling kitchenware at each other to make a dramatic point.

Instead, the film shows (mostly through dialogue) that the key reason their relationship fell apart was far more mundane, with unfulfilled dreams, tragic miscommunication, and the growing responsibilities of parenthood creating a rift that’s far too wide to mend.

The filmmakers hammer this idea home by veering off into outright surrealism at one point, with Willis and Pfeiffer attempting to reconcile in bed before being interrupted by the ghostly apparitions of their parents. A nightmarish scenario, for sure, but it does succinctly illustrate how these characters are products of their own dysfunctional upbringings.

I also respect the fact that there is no clearcut villain in the story. Throughout the runtime, both characters bring up valid critiques of their partner while simultaneously falling prey to their own insecurities and lashing out. This largely leaves it up to the audience to determine who is in the right or wrong, making you feel, in a way, like you are a kid stuck between mom and dad fighting.

Thankfully, Reiner and his team make this difficult-to-stomach material digestible through several methods.

One is the calming soundtrack composed and cultivated by Eric Clapton, which serves as an acoustic balm that soothes any mental abrasions caused by all the marital strife on screen.

Another source of comfort is some well-placed humour.

While there are definitely some clunkers that don’t land, the film has enough clever lines and witty repartee to ensure that the whole enterprise doesn’t get swallowed up by its own self seriousness.

One of my favourite bits comes from Reiner himself, who plays Willis’ close friend and insists at one point that expecting the “perfect” marriage is as delusional as calling the fatty top of our legs an “ass.”

Several scenes later, Willis, who is suffering a mental breakdown, throws this simile back in Reiner’s face by telling him to shove a bread basket “up the tops of your legs.”

Admittedly, this is not the most refined joke in the world. It was even singled out by Roger Ebert in his scathing one-star review of the film as being an example of why this material doesn’t work.

But something about Willis’ screeching delivery and Reiner’s calm look of embarrassment really worked for me, elevating what could have been a disposable, juvenile gag by tapping into some genuine human emotion.

That’s kind of the movie’s entire appeal in a nutshell: unsophisticated and sloppy in places, but undeniably earnest in what it’s trying to accomplish.

This material has undoubtedly been explored in better films, with Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story (2019) and Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight (2013) both providing keener insight into the cataclysmic messiness of a failing marriage.

The Story of Us, while far more scattershot in its execution, at least comes at this difficult subject matter with a great deal of empathy, which is in such short supply these days that I’ll clasp onto anything that attempts to bring a civilizing force back into conversations surrounding relationships.

That humanizing eye is really what made Reiner as a filmmaker, with many of his most famous works eschewing brash cynicism in favour of celebrating the humanity of the characters on screen.

So with that in mind, perhaps it’s time to give The Story of Us another look for those who dismissed it 27 years ago.

It may not be perfect and doesn’t come close to eclipsing Reiner’s outright classics, but watching this movie at least puts the filmmaker’s career, as a whole, into better perspective, which is a worthwhile exercise now that he’s no longer with us.

Verdict:

7/10

Corner store companion:

Ocean Spray Sparkling Pink Cranberry Beverage (because it’s light and refreshing, which should wash the unpleasant taste of a failing marriage out of your mouth)

Fun facts:

-Release date: Oct. 15, 1999

-Budget: $50 million

-Box office: $58.9 million

-Reiner had directed 29 features before his untimely death, with his final film being Spinal Tap II: The End Continues (2025). A follow-up concert film titled Spinal Tap at Stonehenge: The Final Finale was completed and scheduled to be released this year, but has been delayed due to Reiner’s death.

-Both Willis and Pfeiffer were dealing with some serious personal strife at the time of filming. Willis was going through his own divorce with Demi Moore, while Pfeiffer was grappling with her father’s death and the dissolution of her production company (Via Rosa Productions).

–Musical highlight: “Classical Gas” by Mason Williams (plays over a pivotal scene in the third act when one of the characters has an epiphany)

-This film can currently be watched in its entirety on YouTube