When it comes to film criticism, I always try to take my professional life out of the equation, especially when a movie decides to mimic the world I inhabit as reporter.

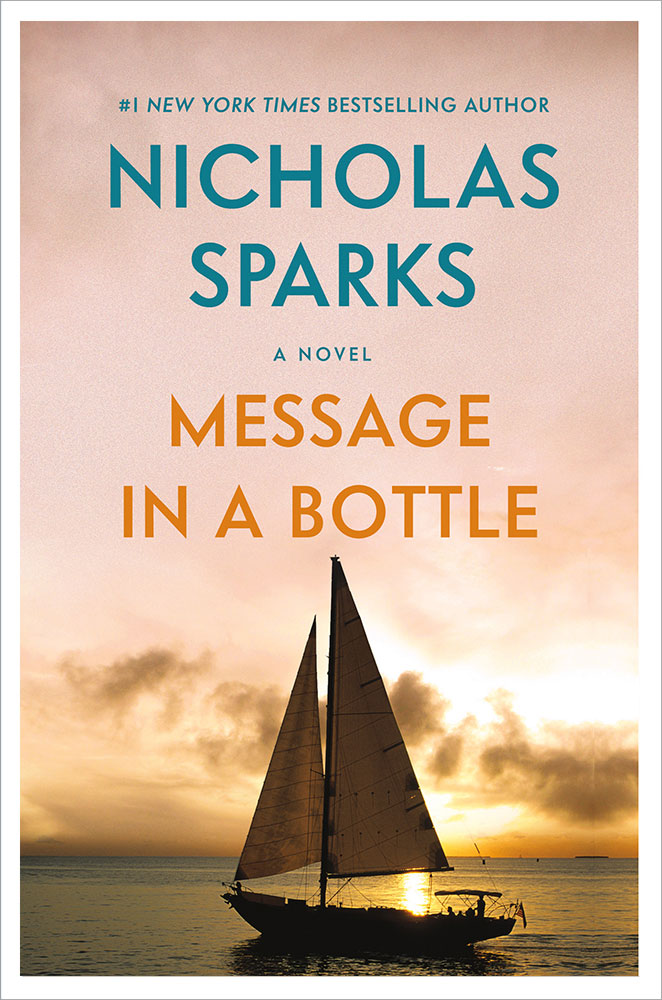

But Luis Mandoki’s Message in a Bottle (1999), based on a novel by Nicholas Sparks, contains such a flagrant example of journalistic malpractice from the main character that I couldn’t help but roll my eyes at what’s otherwise a pretty enjoyable romantic drama.

The film stars Robin Wright as Theresa Osbourne, a researcher for the Chicago Tribune who conducts a nation-wide search for a mystery man after one of his love letters (contained in a bottle, naturally) washes up on the shore of a nearby beach.

Theresa’s search eventually leads her to a sleepy sea-side town in North Carolina, where she comes face-to-face with the author himself: a soft-spoken widower played by Kevin Costner.

Even though Theresa was sent there to gather information on the man (Garrett) and his tragic love story, she neglects to disclose the real reason for her visit, not wanting to spoil the mutual attraction that’s growing between them.

Now, there’s a lot wrong with this set-up on multiple levels.

In terms of journalistic ethics, Theresa failing to divulge her true assignment to Garrett from the get-go is incredibly sketchy, since she’s gathering sensitive details about a man’s dead wife under false pretenses.

This approach might have made sense if the character worked for a scuzzy tabloid newspaper that is completely devoid of editorial scruples.

But in the real world, even the gutter trash “reporters” that work for TMZ announce who they are when they harass celebrities at the airport, so I don’t know why Sparks and screenwriter Gerald Di Pego decided to portray the Chicago Tribune staff in such a negative light (intentionally or not).

On a writing level, this deceitful action also drags down Wright’s otherwise solid lead performance as Theresa, who is meant to be this kind, empathetic figure but just comes across as being manipulative.

No matter how many times she shares a cute moment with Garrett or even his crusty father Dodge (played by Paul Newman), I couldn’t get invested in these relationships since they are built on a foundation of lies.

Of course, it’s obvious why they decided to include this plot element in the story: to build tension.

Theresa’s deception serves as a kind of Sword of Damocles for the narrative, something that hangs over the central romance and threatens to destroy it at any second.

And while every good love story needs tangible conflict beyond a “will they, won’t they?” dynamic, a seemingly good-hearted person lying to a grieving widower by omission seems like the laziest possible way to inject that sort of speed bump into the plot.

In my view, Message in a Bottle (1999) would be vastly improved if Theresa simply revealed her intentions to Garrett from the outset.

Not only is this approach more consistent with how the character is written, but it also provides a much more interesting avenue for conflict, where she gradually has to win Garrett’s trust as both a reporter and romantic partner throughout the course of the story.

I know my fixation on this one plot point is a little over-the-top, but that’s only because it drags down a movie that I really wanted to like.

After all, this is my first time indulging in a Nicholas Sparks story, and it’s easy to see why his specific slice of romantic fiction has spawned such a vast media empire on the printed page and silver screen.

For one thing, the film’s cinematography is consistently gorgeous, with Oscar-nominated DP Caleb Deschanel doing an expert job of capturing the beauty of costal America that Sparks loves to write about.

Some lingering shots of sailboats and crashing ocean waves might wander into the territory of scenery porn, but that at least has some relevance to the plot, reinforcing Theresa’s desire to abandon her life in the big city to live with Garrett.

This idyllic, small-town atmosphere is made even more appealing thanks to a really strong supporting cast, who come across as the exact kind of people you would want to chat up after checking into a bed and breakfast.

Paul Newman really shines in this capacity, with his character’s salt-of-the-earth wisdom and sassy comebacks leading to some of the film’s best moments.

Plus, the movie’s soundtrack features a bevy of easy-listening icons like Faith Hill, Sheryl Crow and Sarah McLachlan, which compliments this laid-back aesthetic in a very meaningful way.

Of course, Message in a Bottle has a couple other things holding it back aside from a single questionable writing decision at its core.

For one thing, the film’s runtime clocks in at over two hours, which is way too long for this kind of movie and it really kills the momentum in the third act.

You’ll also notice that I haven’t commented on Costner’s qualities as a romantic lead up until this point, and that’s because he barely registers as a presence on screen.

I understand that it’s difficult to squeeze a compelling performance out of a character who is meant to emotionally withdrawn, but Costner never really manages to get himself out of first gear, even when he’s asked to deliver a passionate monologue later on in the movie.

It’s almost like he suffers from the reverse problem of his co-star (Wright), since Costner’s wooden acting doesn’t compliment some admittedly solid character writing from Sparks and Di Pego.

Unfortunately, these two incomplete characters don’t coalesce into a compelling whole, which is a big problem when your romantic leads are the movie’s biggest selling point.

Despite this film’s mixed quality, it still hasn’t discouraged me from watching the remaining four entries in my “5 Film Collection: Nicholas Sparks” DVD set.

Clearly the author has tapped into a formula that resonates with a lot of people—having sold over 115 million copies of his books worldwide—and I’m curious to see if the more appealing qualities of Message in a Bottle (1999) are way more prevalent in future film adaptations.

But hopefully this story marks the last time Sparks dips his toes into writing about the world of journalism, since he’s clearly out of his depth when it comes to this subject.

Verdict:

5/10

Corner store companion:

Sensations Cracker Assortment (because this is possible one of the whitest movies I’ve ever seen)

Fun facts:

-Release date: Feb. 12, 1999

-Budget: $80,000 (estimated)

-Box Office Gross: $52,880,016 (domestic), $118,880, 016 (international)

–Message in a Bottle is the first of 11 total Nicholas Sparks film adaptations. Altogether, these movies have grossed a combined $ 889,615,166 worldwide.

-While all of Sparks’ films manage to turn a profit, none of them are critical darlings. Out of all 11 movies, The Notebook has come the closest to achieving a “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes at 53 per cent.

-Sparks originally published Message in a Bottle back in 1998. It was his second official novel after The Notebook in 1994.

-Sparks’ most recent written work, The Return, was released back in September of this year, which marked his 21st published novel. He’s also written two non-fiction books.

-Kevin Costner was nominated for a Golden Raspberry Award (Worst Actor) in 2000 for his performance in both Message in a Bottle and For The Love of the Game.

-Musical highlight: “Carolina” by Sheryl Crow (plays over the end credits)